And other things we learned from four years’ worth of Netflix Viewership data tied to content spend

By Hernan Lopez. Companies mentioned: AMC, Banijay, Disney, HBO, NBCU, Lionsgate, Netflix, North Road, Paramount, Sony, Warner Brothers, YouTube.

Questions answered: Which studio accounts for 8% of Netflix’s Viewing Hours? Which country of production is most cost efficient at scale relative to viewership? Is film viewership on Netflix going up or down?

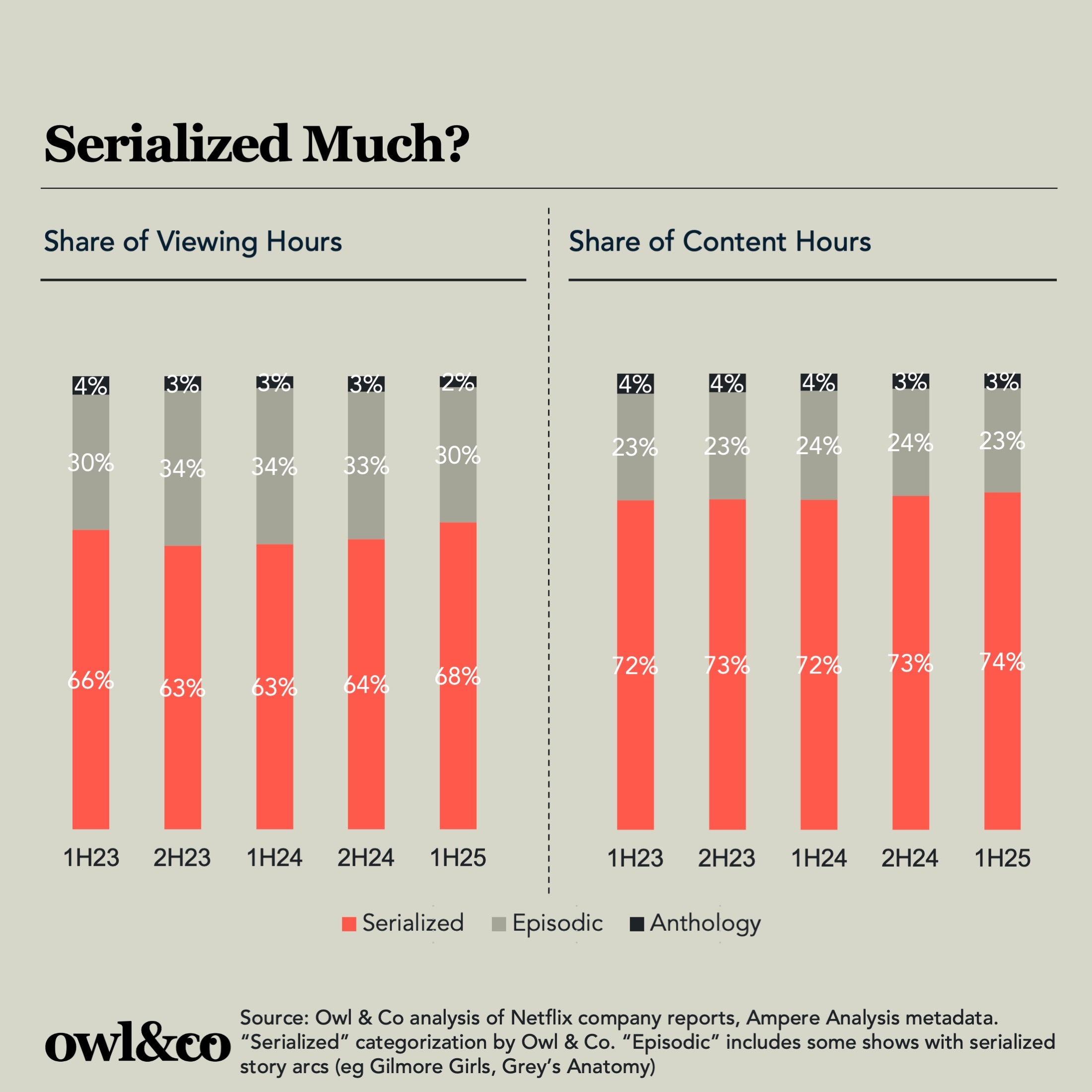

Back in 2013, when Netflix declared it needed to “become HBO,” it set the tone for the kind of shows it, and other streamers, would chase for years to come. Character-driven. Cinematic. Highly serialized.

But also: expensive and time consuming to make. Freed from broadcast constraints like ad breaks or fixed seasons, serialized shows—especially limited series—became magnets for A-list actors who wanted prestige without long-term commitments. It was a win-win for the streamers, as limited series were buzzy, awards-worthy, and considered acquisition drivers.

The ‘peak TV’ bubble and its second-order effects have been widely covered—but I do have some data that hasn’t been previously reported...